Building Trust, Leadership Skills with EdTech

By Kristi DePaul

In an era of ever-increasing transparency, companies are acknowledging that trust is powerful organizational currency.

Wake Forest Associate Professor Holly Brower agrees. She believes that trust cannot be overemphasized in business relationships.

Brower’s research, which has been cited by leading academic and trade journals, has focused on leadership and trust. That is, the elements critical to developing business relationships and examining how trust influences interactions between bosses and subordinates. Productivity, employee engagement and satisfaction, and profits are definitely at stake.

She explains that while her research remains an integral part of her career, she is first and foremost an educator.

“At Wake Forest, we’re very committed to the teacher-scholar model. Scholarship is a way of informing our teaching and making our teaching relevant, connecting it to the marketplace and emerging knowledge.”

Speaking of trust—when it comes to edtech, Brower explains that she is ‘always skeptical.’

“Faculty members are under constant bombardment in terms of sales pitches. I was on the editorial board of an academic journal when ForClass caught my attention. A friend of mine (and star professor) sent an email and said ‘I used ForClass last semester, it’s a great tool and there’s nothing else like it’—adding that it was a great way to lead class discussions.”

Brower felt that it sounded too good to be true, but because of the enthusiastic endorsement, she decided to give it a try. She sent the ForClass team her syllabus and went on to pilot test it with one undergraduate class.

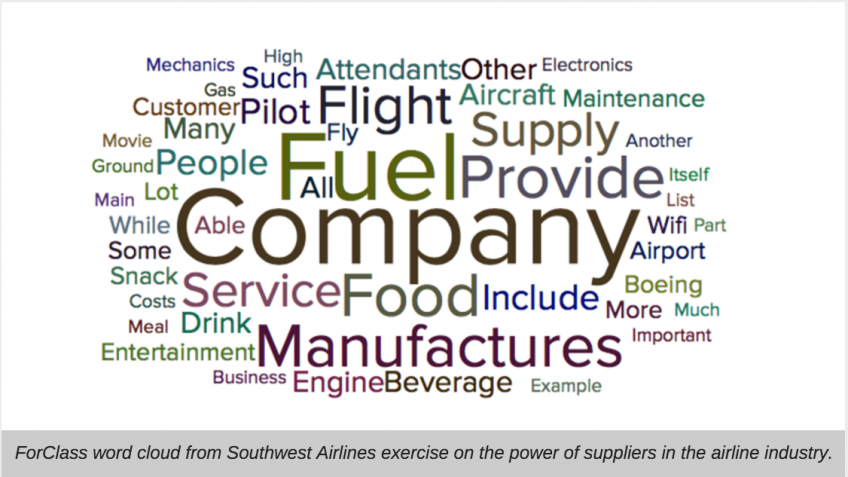

“Their support was great. The ForClass folks found articles and inserted cool icons to make the user experience more attractive to students. Immediately after rolling it out, I liked the way I could use the platform to encourage discussion.”

Support went beyond the tech perspective; Brower also benefited from ForClass co-founder Gad Allon’s pedagogical perspective as a full professor at Kellogg School of Business.

“With Gad’s coaching, I’ve been able to look at my lesson plans and determine where the discussion should go. I then work backwards, asking my students a series of questions so that their answers lead it there.”

Sign up now to try ForClass today, or learn more through a demo with co-founder Prof. Gad Allon.

Brower uses ForClass in an undergrad senior seminar on leadership and an MBA course in organizational behavior. She doesn’t use a textbook for either course, but instead employs a collection of readings and cases, which are gathered into a hub of easily accessible content on the ForClass dashboard.

She informed her students that this was an edtech experiment of sorts, and they were the guinea pigs. Their responses? Brower’s students said that ForClass makes them ‘prepare for every class,’ and that they ‘can never slack off.’ Her MBA students are now accustomed to actively defending their positions or interpretations of the reading.

Brower has taken care to remind all of her students that the classroom is a safe space—a ‘no humiliation zone’. She believes that ForClass is a way for her to hold them accountable in a more strategic fashion than cold-calling on students or depending upon them to volunteer answers.

“My courses are 80 percent discussion based, with very little lecturing. Occasionally, discussions have gone far afield from the key points I wanted to make during class. Before ForClass, whenever there were four hands in the air, I didn’t have a clue where each student might take the discussion. This is where I’ve seen a huge improvement: with certain parameters in place, I know ahead of time that [for example] I really want Vanessa to share her specific perspective, even if her hand isn’t up.”

She uses coaching as a teaching model, believing that one learns to lead by leading. The experiential nature of her courses sometimes goes well beyond the classroom’s four walls; recently, one of her classes completed a two-and-a-half hour ropes course. They reflect on what they’ve learned, and what principles can be translated to issues they might encounter as leaders.

Over the course of a semester, Brower’s undergraduate students pick a legacy project; a sustainable venture intended to live on beyond their years at Wake Forest.

“I tell my students that I want them to think about leading for the purposes of this class. Sure, we’re all high achievers in this context. But we must inspire, motivate, guide and structure other people’s work to achieve a common goal.”

How does ForClass play into that?

“A lot of my job is coaching them in that process. ForClass allows me to better lead my class discussions, and to hold my students accountable. They’re learning principles of leadership and discussing them so they can then put them into practice.”

Discussion-based classes depend upon interactivity, and when everyone participates, they thrive.

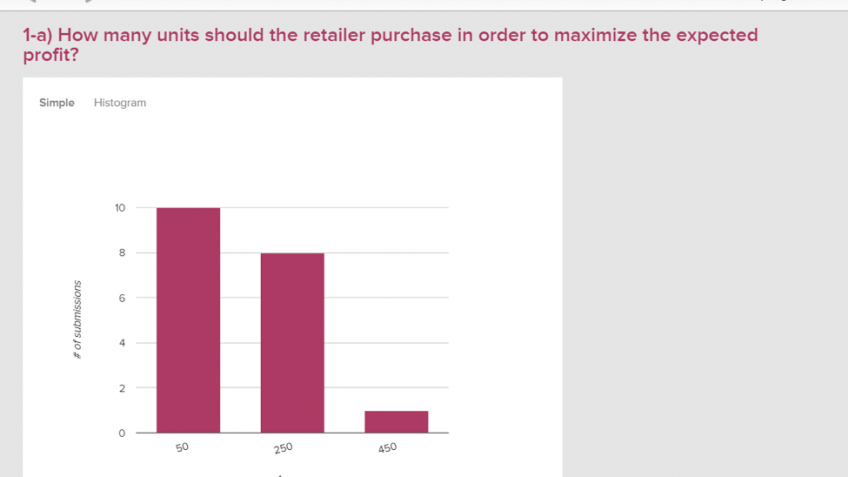

“I know what each of my students’ voices sounds like. When I click on a bar chart and say we’re going to talk about this, they’re anxious to see results. You can see their anticipation. They want know where they fall. And when all of their pictures show up on the screen, I’m not going to call on the person who always talks with ease. I’ll instead bring another student into the conversation, ‘so Tyler, we haven’t heard from you…’”

Brower doesn’t discount the ways in which her students can teach one another, either.

“Students learn from one another so much—especially in a graduate level class, I feel very strongly that you often learn more from your peers than from a professor. ForClass facilitates that, so students hear others’ experiences and perspectives that play into the topic of the day. I don’t want them to miss their own perspectives. Now I know exactly where to ask each student to share his or her thoughts.”

—

Dr. Holly H. Brower joined the Wake Forest University faculty in July 2005. She is currently the Faculty Advisor for Internships for the Business and Enterprise Management Major. She teaches Organizational Behavior, Leadership, Leadership in the Nonprofit Sector, and Leading Change.

- Check out the ForClass video gallery or read other faculty members’ perspectives in our recent blog posts.